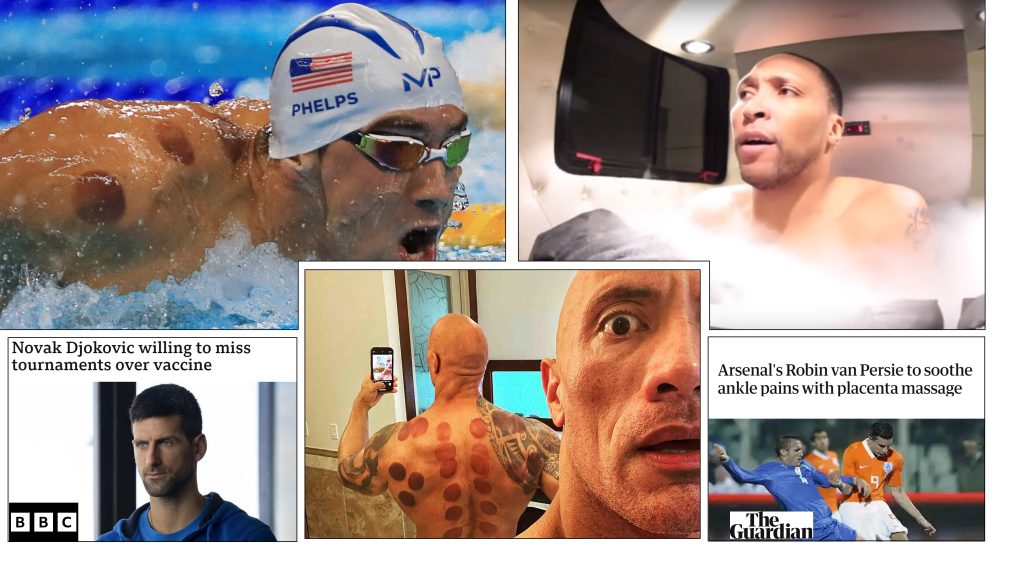

Earlier this year, the world’s most successful male tennis player, Novak Djokovic, was deported from Australia—not for misconduct on the court or for doping, but for violating Australia’s border policy that mandated COVID-19 vaccinations.1 Djokovic is one of many professional athletes who have refused the vaccine, a list that includes Czech tennis player Renata Voráčová; NBA players Kyrie Irving and Jonathan Isaac; American golfer Bryson DeChambeau; and professional footballers Aaron Rodgers, Cole Beasley, Vernon Butler, and Star Lotulelei.

These high-profile cases may not represent the broader perspectives of professional athletes (major sports leagues including the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the Woman’s National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League reported COVID-19 vaccination rates nearing 100 percent), but it did have the media questioning why some elite athletes have been reluctant to get the COVID-19 vaccine and whether they might be susceptible to pseudoscience in general.

This question surfaced in an interview I gave at the time of Djokovic’s deportation, and I had to admit that, when it comes to embracing superstition and pseudoscience, professional sports doesn’t have a good reputation.

Consider Tom Brady, regarded by many as the greatest NFL quarterback in history. In his bestselling book, Brady attributes his incredible longevity to the concept of “muscle pliability”—a widely discredited term conjured by Brady’s self-taught exercise guru who has twice been investigated by the FTC for making fraudulent health claims, once while impersonating a doctor. But muscle pliability is just the tip of a pseudoscience iceberg. The remainder of Brady’s empire comprises his “TB12” brand, a system of restrictive diets, alkaline foods, and immune-boosting supplements.

Just a few years after Brady launched TB12, Michael Phelps—the most successful Olympian in history—was making a splash (pun intended) with his unwitting promotion of cupping therapy. In a typical session, sore or injured muscles are covered with small glass cups in which suction is created using a device or a heated mechanism. As an “energy medicine,” cupping has been denounced by the scientific community, and there are numerous reports showing no benefit beyond basic placebo (Lee, Kim, and Ernst 2011) and evidence of cupping related burns. In the swimming finals at the Rio Games (2016), when Phelps revealed circular bruises across his back and shoulders, I knew his endorsement would have a ripple effect (pun unintended) on the sport for many years to come.

Whole-body cryotherapy is another alternative practice that’s been popularized by high-profile athletes, including LeBron James and Floyd Mayweather, on the premise that it reduces muscle and joint inflammation. In a typical exposure, the athlete enters an upright tank about the size of a large closet, in which the air has been cooled to between −150°C (−238°F) and −200°C (−328°F). Athletes use cryotherapy on the basis that it “speeds recovery, relieves soreness, reduces lactic, and helps inflammation,” but the scientific evidence shows no such mechanism. Still, in today’s wellness culture, marketing rhetoric and celebrity endorsements are a runaway train (and scientific data is a wooden fence blocking its path). Cryotherapy has become a mainstay in professional sports, embraced by teams in the NFL, NBA, and professional soccer. It’s been used by National Sports Centers around the world, and the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) have partnered with an official cryotherapy sponsor.

A final, more radical example of high-profile pseudoscience in sports is Robin van Persie’s efforts to return from an injury he sustained in 2009. To expedite his recovery, the soccer player (now retired) visited a physiotherapist who massaged horse placenta onto his injured ankle. “It cannot hurt,” said van Persie at the time, “I have been in contact with Arsenal physiotherapists, and they have let me do it.” There’s no scientific consensus on the benefits of horse placenta for ligament injury nor is there a plausible mechanism of action. But van Persie’s statement offers a lucid insight into the motives behind his decision: i.e., What’s the harm?

Are We Dealing with Institutionalized Pseudoscience in Sports?

There are swathes of athletes (perhaps the majority) who do not routinely use alternative therapies or other pseudosciences, instead preferring evidence-based approaches. Sportspeople tend to be data-driven, which one could speculate lends itself to a mindset of quantitative empiricism. There’s also the issue of motive. When placebo products are used, it’s rarely because of an athlete’s desire to subvert mainstream practice, to embrace alternative (implausible) mechanisms that revolve around energy medicine and witchcraft, or because of a dissatisfaction or distrust in conventional science and societal norms.

Instead, it could be argued that athletes and coaches have unintentionally curated a culture in which pseudoscience can thrive. In high level sports, no performance advantage is too small. This is the premise underpinning marginal gains—small improvements in several different aspects leading to cumulative increases. When the difference between gold and silver can be infinitesimally small, all treatments (evidence based or those that are known to work only via placebo) are thrown in the melting pot of possibilities, justified by the notion that every percentage point counts. It’s unsurprising that athletes and their coaches will pursue any advantage they can, regardless of how alternative it may seem.

In some ways, this is pseudoscience at its most insidious. Contemporary pseudoscience, even that based on the most extremely obscure principles, is marketed using congenial terminology and laced with just enough science and plausibility, and marketed with just the right “spin,” that it slips through the nets that have been cast by well-meaning sportspeople. Thus, it snakes its way into daily practice, becoming intermingled with evidence-based interventions until it’s difficult to tell them apart.

Research suggests that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is highly pervasive in sports, mostly for treating musculoskeletal injuries (Malone and Gloye 2013; Ernst 2004). In fact, while data from the CDC suggest that approximately 40 percent of Americans use alternative therapies (Barnes, Bloom, and Nahin 2007), use by athletes may be as high as 50–80 percent (Nichols and Harrigan 2006; Youn, Ju, Joo, et al. 2021; Pike 2005; White 1998). To my knowledge, no studies have compared the prevalence of pseudoscience between amateur and professional sports, but in the NFL, for example, 77 percent of athletic trainers have referred players to a chiropractor for assessment and/or treatment, and around one-third of NFL teams have a chiropractor on their payroll (Stump and Redwood 2002).

So, yes—I think pseudoscience is a systemic problem in sports, just as it is in popular culture.

Actions of the Few

While it goes without saying that the high-profile cases of pseudoscience described above are not necessarily representative of the entire athletic field, these celebrities are leaders in their respective domains. Whether or not they readily admit it (and I’m fairly sure most of them would), revered athletes have a profound influence on their peers and athletes of lesser ability. More importantly, the general population tend to be drawn into the athlete’s immense gravitational field; watching their performances, following their social media feeds, even deifying them for their talent. The actions of the few therefore have downstream effects on the many. This is the essence of population trends in CAM, and elite athletes are known for setting them.16

We can test this empirically. When Phelps introduced the mainstream to cupping in 2016, piquing their interest (or renewing their interest) in this ancient Chinese medicine, cupping therapy’s Wikipedia page saw an enormous spike in traffic, from an average of around 1,500 per day to well over 100,000. This may not be causal, but if it’s just correlation then it’s a fascinating coincidence. Consequently, people who may never have otherwise heard about this widely discredited practice were learning of its techniques and purported applications. How many of those people went on to source a cupping therapist of their own? We can see a similar pattern in Wikipedia searches of therapeutic tape, which was also featured heavily in the 2016 Olympic Games.

But the athletes themselves should not be blamed for these statistics. Athletes are (generally) not scientists, and we cannot expect them to behave as such. Most athletes in the West, especially at the elite level, are advised by coaches and supported by a network of physicians, physiologists, nutritionists, and psychologists. Some athletes follow their coach’s advice so blindly that they would take an “unknown supplement” from them without questioning its effects or legal status (Bérdi et al. 2015). It wouldn’t have mattered quite so much if Phelps’s cupping, Brady’s muscle plasticity, and van Persie’s horse placenta had been immediately and decisively denounced by their respective advisors. But this never came to pass. It’s largely because of such failures to hold these prize athletes accountable for their nonsense that these “therapies” endure in sports. Even physicians aren’t blameless, with 88 percent of physician members of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine prescribing at least one type of CAM for sports medicine pathologies in the preceding year, mostly chiropractic, acupuncture, and yoga (Kent et al. 2020). This all speaks volumes about the perceived importance of placebo effects in high performance sport.

The Power of Placebo

And not unduly. Placebos have long been known to have very powerful psychobiological effects. For example, placebos can delay muscle fatigue and improve performance (Pollo, Carlino, and Benedetti 2008) and partly contribute to the performance enhancing effects associated with nutritional supplements (Marticorena, Carvalho, Oliveira, et al. 2021). Endurance-trained adults, injected with an inactive substance that they believed to be a powerful supplement, showed significantly improved distance running performance (Ross, Gray, and Gill 2015). As a result, unproven (and sometimes disproven) practices are not necessarily being used in sport because of science illiteracy and superstition; they’re often used because coaches, athletes, and support staff know they work.

Around 44 percent of sports coaches, from regional to international levels, admitted trying to influence their athletes’ performances using placebos (Szabo and Müller 2016) and the number was nearer 60 percent at the elite level. From an athlete’s perspective, a small survey of competitive, international, and professional athletes revealed that the majority (97 percent) believe that the placebo effect exerted an influence on sports performance; moreover, 73 percent said they had experienced what they defined as a placebo effect. Some people consider psychological advantages in sports to be more important than physical ones, and research shows that mental training in addition to physical training can improve results much more than physical training alone (Kumar and Shirotriya 2010) For this reason, most elite athletes (67 percent) when surveyed said they would happily engage in a placebo-mediated deception as long as it improved their performance (Bérdi et al. 2015).

Consequences

Of course, widespread acceptance of placebos in sports, for the sake of athletic performance, gives no consideration to its potential downstream consequences. Consider that Phelps’s cupping is used widely to attenuate muscular aches and pains, but serious proponents advocate the therapy for asthma (among other ailments). It shouldn’t need stating, but please do not attempt to treat asthma with cupping therapy. James’s cryotherapy, in the sporting arena, tends to be used to suppress inflammation that results from hard training, yet many vendors promote it as a cure for various diseases. Brady’s pseudoscience empire comprises supplements and “alkalizing” and “anti-inflammatory” foods that, according to the man himself, can “lower pH levels” and “help with a range of ailments, from boosting low energy to preventing bone fracture.” And I doubt the reader needs a reminder of the damage and chaos wrought by the anti-vaccine rhetoric stoked by Djokovic and others. Pseudoscience in sports has profound consequences on population health and clinical practice.

And there may be direct implications for sports. As with non-athlete patients, many athletes perceive alternative therapies to be more “natural” than mainstream medicine and, therefore, less likely to contravene the anti-doping code as either a method or a substance. This would be a grave mistake. Many CAMs are pharmacological agents, and a failure to recognize this puts athletes at risk of inadvertent doping (Koh, Freeman, and Zaslawski 2012).

Conclusions

Pseudoscience preys on hopes and fears—two sides of the same coin—and it also feeds on desperation. Because of the “win at all costs” mentality nurtured in high-performance sports, athletes exhibit plenty of all three traits. And such characteristics likely become intensified closer to elite level. Even though many athletes prefer evidence-based approaches, it only takes a minority of individuals, especially those who are famous or revered, to allow for the spread of misinformation and erroneous advice. Moreover, there’s little doubt that the culture of high-performance sport may be allowing pseudoscience to breed unabated, generally unchallenged by athletes, coaches, and scientific support staff, all on the justification of important placebo effects. But widespread acceptance of placebos in sport gives no mind as to how these products affect the masses when they bleed into mainstream practice. Indeed, we now have decisive answers to the question of “What’s the harm?”

References

Barnes, PM, Bloom, B, and Nahin, RL. 2007. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children: United States (623942009-001). Published online 2008. doi:10.1037/e623942009-001.

Bérdi M, et al. 2015. Elite athletes’ attitudes towards the use of placebo-induced performance enhancement in sports. Eur J Sport Sci. 2015;15(4):315-321. doi:10.1080/17461391.2014.955126.

Ernst, E. 2004. Musculoskeletal conditions and complementary/alternative medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 18(4):539-556. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2004.03.005.

Kent, JB, et al. 2020. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Prescribing Practices Among Sports Medicine Providers. Altern Ther Health Med 26(5):28-32.

Koh B, Freeman L, and Zaslawski C. 2012. Alternative medicine and doping in sports. Australas Med J 5(1):18-25. doi:10.4066/AMJ.20121079.

Kumar, P, and Shirotriya, AK. 2010. ‘Sports psychology’ a crucial ingredient for athletes success: conceptual view. Br J Sports Med 44(Suppl 1):i55-i56. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.078725.186.

Lee MS, Kim JI, and Ernst E. 2011. Is cupping an effective treatment? An overview of systematic reviews. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 4(1):1-4. doi:10.1016/S2005-2901(11)60001-0.

Malone, MA, and Gloyer K. 2013. Complementary and alternative treatments in sports medicine. Prim Care 40(4):945-968, ix. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.08.010.

Marticorena FM, Carvalho A, Oliveira LFD, et al. 2021. Nonplacebo Controls to Determine the Magnitude of Ergogenic Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 53(8):1766-1777. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002635.

Nichols, AW, and Harrigan, R. 2006. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Usage by Intercollegiate Athletes. Clin J Sport Med 16(3):232-237.

Pike, ECJ. 2005. ‘Doctors Just Say “Rest and Take Ibuprofen”’: A Critical Examination of the Role of ‘Non-Orthodox’ Health Care in Women’s Sport. Int Rev Sociol Sport 40(2):201-219. doi:10.1177/1012690205057199.

Pollo A, Carlino E, and Benedetti F. 2008. The top-down influence of ergogenic placebos on muscle work and fatigue. Eur J Neurosci 28(2):379-388. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06344.x.

Ross R, Gray CM, and Gill JMR. 2015. Effects of an Injected Placebo on Endurance Running Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 47(8):1672-1681. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000584.

Stump, JL, and Redwood, D. 2002. The use and role of sport chiropractors in the national football league: a short report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 25(3):E2. doi:10.1067/mmt.2002.122326.

Szabo, A, and Müller, A. 2016. Coaches’ attitudes towards placebo interventions in sport. Eur J Sport Sci 16(3):293-300. doi:10.1080/17461391.2015.1019572.

White, J. 1998. Alternative Sports Medicine. Phys Sportsmed 26(6):92-105. doi:10.3810/psm.1998.06.1066.

Youn BY, Ju S, Joo S, et al. 2021. Utilization of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Korean Elite Athletes: Current Status and Future Implications. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021:e5572325. doi:10.1155/2021/5572325.